Spinal Dysraphism

Spinal Dysraphism

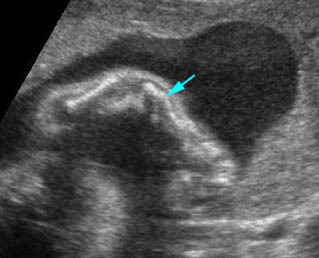

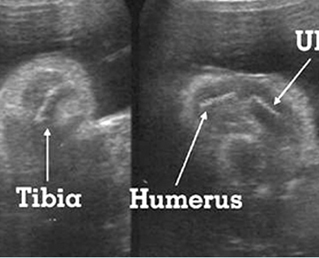

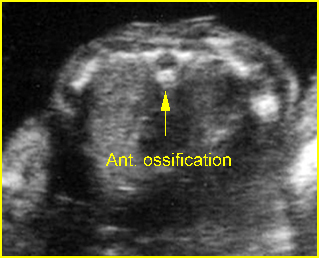

Spinal dysraphism, splaying of the posterior ossification centers of the spine, usually indicates spina bifida resulting from failure of closure of the posterior neuropore. However, spinal dysraphism can be due to other abnormalities as follows:

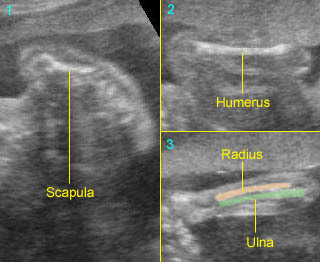

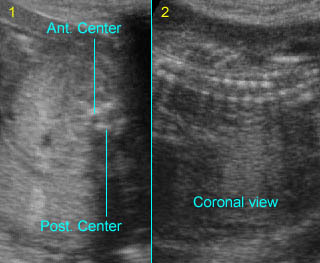

Fig 1, Fig 2, Fig 3

Major differential diagnoses

- Spina bifida

- meningocele

- meningomyelocele

- myeolochisis

- Arnold-Chiari malformation type II

- Pseudodysraphism: technical pitfalls (described previously)

Minor differential diagnoses

- Diastematomyelia: a splitting of the spinal cord

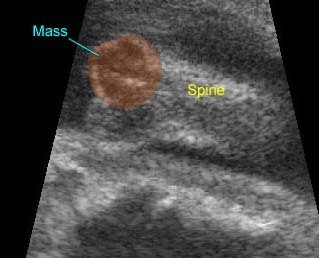

- Lipomyelomeningocele: asymmetric lesion of lipoma originating in the spinal cord or cauda equina

- etc.

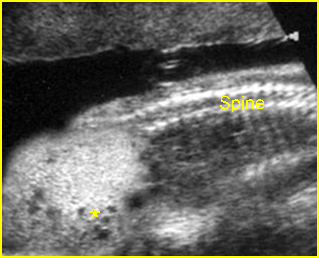

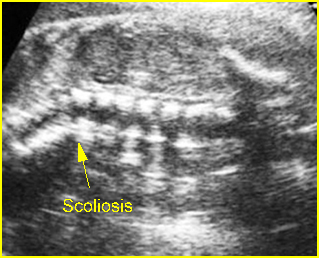

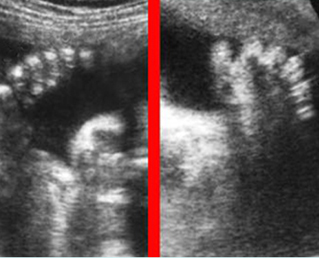

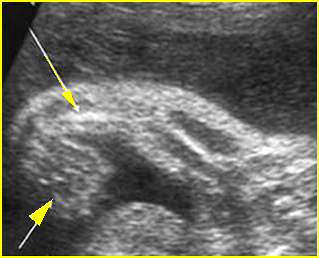

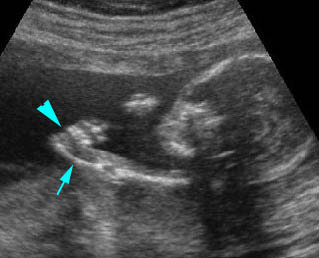

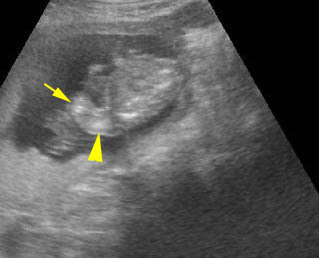

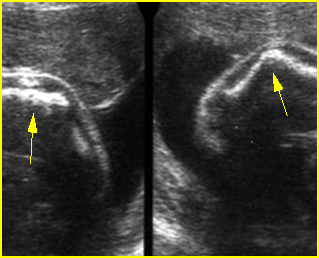

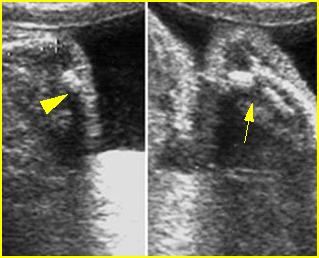

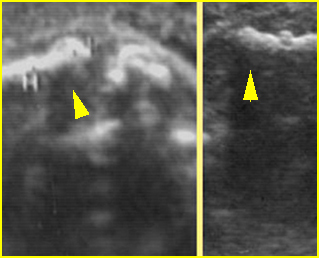

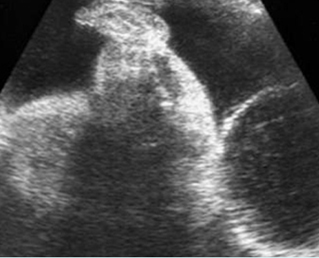

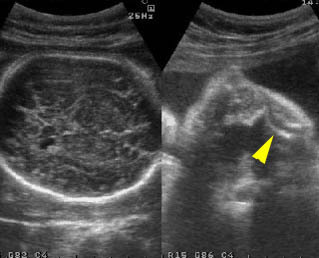

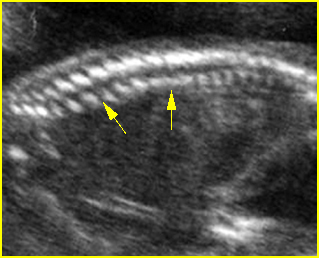

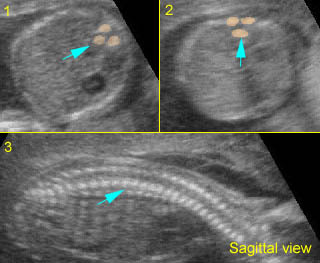

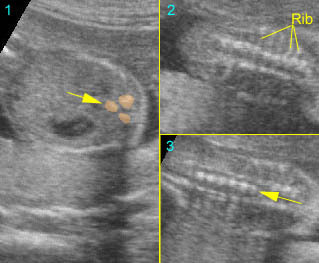

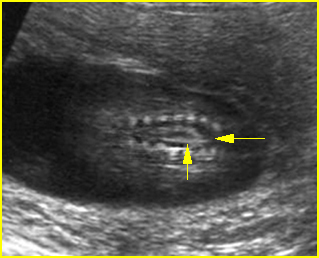

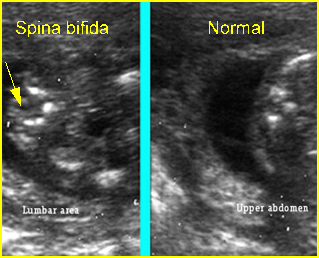

Fig 1: Spina bifida Cross-sectional scan of the lumbar and thoracic spine: separation of posterior ossification centers at the lumbar region with small protrusion of the overlying tissue

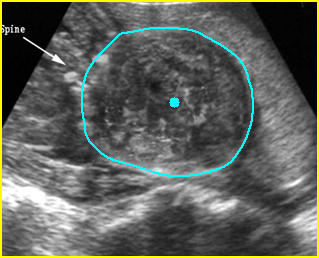

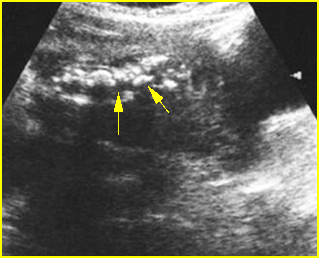

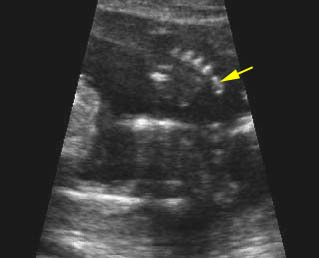

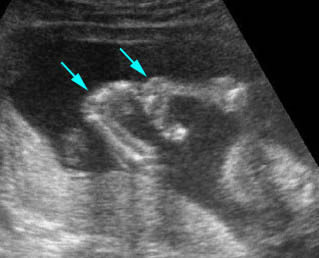

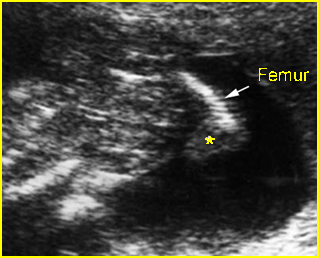

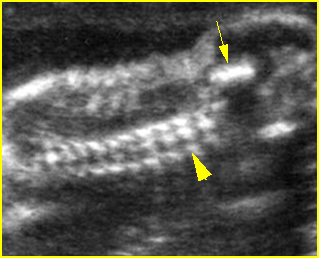

Fig 2: Spina bifida Coronal scan of the lumbosacral spine: separation of the ossification centers of the spine (arrow)

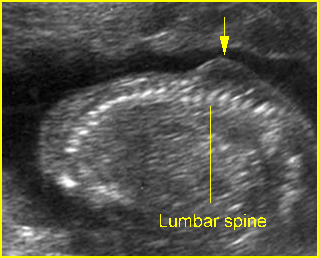

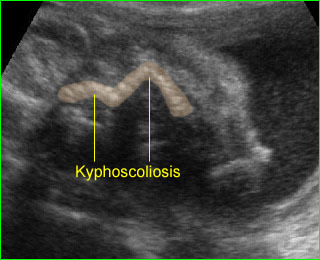

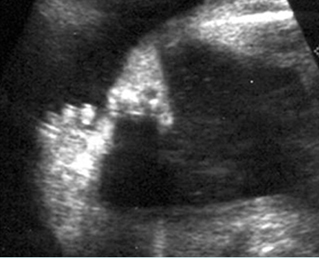

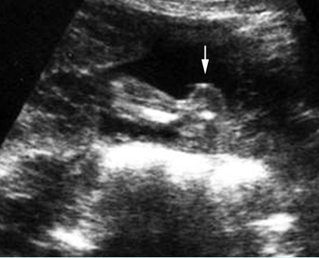

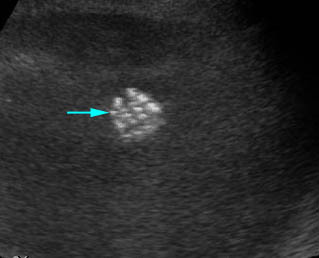

Fig 3: Spina bifida Cross-sectional scan of the lumbar and thoracic spine: separation of posterior ossification centers at the lumbar region with small protrusion of the overlying tissue (arrow)

Video clips of spinal dysraphism

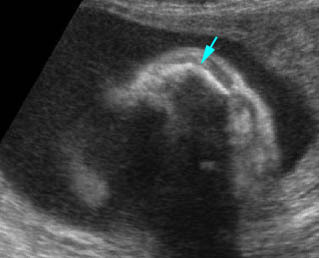

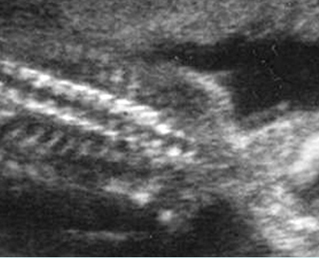

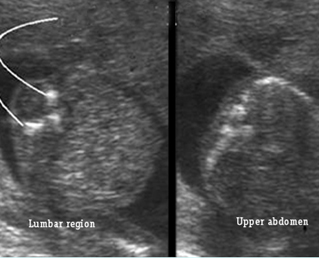

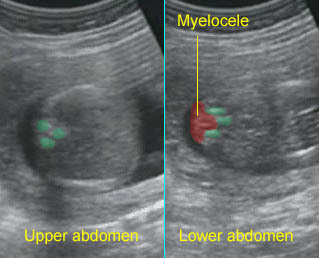

Spina bifida : Cross-sectional scan of the normal spine at the level of upper abdomen, but wide separation of the posterior ossification centers at the lumbar spine with the protrusion of the spinal cord

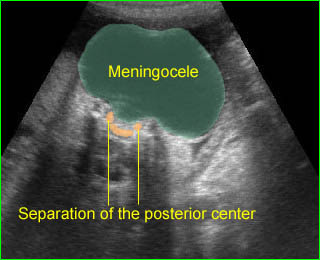

Large meningocele : Cross-sectional scan of the normal spine at the level of upper abdomen, but wide separation of the posterior ossification centers at the lumbar spine with the protrusion of the meningeal sac